Exploring the True Bloodline of Indian Freedmen: A Historical Perspective

- @Ronicaronica

- Jul 22, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2024

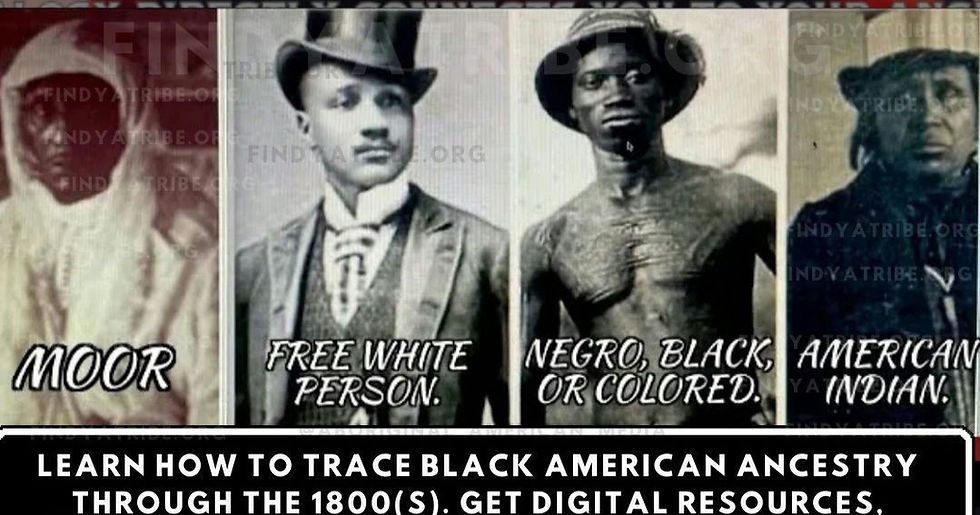

The historical narrative surrounding Indian Freedmen is complex and often misunderstood. Many contemporary discussions frame Indian Freedmen—descendants of African slaves owned by Native American tribes—as lacking legitimate claims to indigenous heritage. However, a closer examination of historical practices reveals that many individuals labeled as Indian Freedmen may actually possess a direct indigenous lineage, rooted in the practice of Native American tribes capturing and enslaving other indigenous peoples during intertribal conflicts. This article seeks to explore this perspective, supported by scholarly research, to better understand the intricate dynamics at play.

Historical Context of Indian Freedmen

The term "Indian Freedmen" generally refers to individuals of African descent who were enslaved by Native American tribes, particularly the Five Civilized Tribes—Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole. Following the Civil War, these tribes were compelled by the U.S. government to emancipate their slaves and integrate them into their societies as citizens. However, this simplistic categorization overlooks the multifaceted history of slavery and conflict among indigenous tribes.

Intertribal Conflicts and Indigenous Enslavement

Intertribal warfare and the practice of capturing and enslaving members of rival tribes were prevalent among many Native American societies long before European contact. Captives were often absorbed into the captor tribes, sometimes as slaves and other times as fully integrated members. This historical reality is well-documented. For instance, historian Robbie Ethridge notes that during the colonial period, the Creek and other southeastern tribes engaged in extensive raiding and capturing of individuals from rival tribes, incorporating them into their own communities (Ethridge, 2003).

The Enslavement of Indigenous Peoples by Native American Tribes

The introduction of African slaves into Native American societies further complicated these dynamics. Some tribes, already accustomed to the practice of holding war captives as slaves, began to incorporate African slaves into their communities. However, it is critical to distinguish between the enslavement of Africans and the pre-existing practice of capturing and enslaving indigenous individuals.

Re-examining the Label of Freedmen

Given this historical context, many so-called Indian Freedmen may actually be descendants of indigenous captives who were erroneously classified as African due to the presence of African slaves within these tribes. This misclassification served to further disenfranchise these individuals and obscure their true heritage.

Scholarly Insights on Misclassification and Disenfranchisement

The scholarly work of Tiya Miles highlights the complexities of identity among Indian Freedmen, emphasizing the fluidity and contested nature of racial and ethnic boundaries in Native American societies (Miles, 2005). Miles points out that the U.S. government's rigid racial classifications often failed to capture the nuanced identities of people who straddled multiple heritage lines.

Furthermore, research by Barbara Krauthamer reveals how the legal and social structures imposed by the U.S. government, including the Dawes Rolls, often misrepresented the ancestry of individuals, categorizing them in ways that served political and economic interests rather than reflecting their true lineage (Krauthamer, 2013).

Conclusion

The historical narrative of Indian Freedmen is not simply one of African slaves integrated into Native American tribes. Instead, it is a complex tapestry of intertribal conflicts, indigenous enslavement, and the subsequent misclassification and disenfranchisement of individuals with legitimate indigenous heritage. By re-examining these histories through a scholarly lens, we can better appreciate the true bloodline of Indian Freedmen and challenge the erroneous labels that have been imposed upon them. This nuanced understanding is crucial for recognizing the rightful heritage and identities of these individuals, whose stories have been marginalized and misunderstood for far too long.

References

Ethridge, R. (2003). Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World. University of North Carolina Press.

Miles, T. (2005). Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. University of California Press.

Krauthamer, B. (2013). Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South. University of North Carolina Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments